DevOps Plan – Requirements from Funnel to Scrum board

Gerelateerde artikelen

Introduction Funnel to Scrum board

This article describes some best practices on the funnel and the requirements in a DevOps context. The terms used in this article could be defined differently on the Internet or in other methods. Because there are no unambiguous definitions and since they are of great significance for this best practice article, these terms are defined first before the article starts. It turns out in practice that these terms are very easy to imbed in tools and easy to learn.

Definitions for DevOps Plan

Theme

A theme describes an innovation that is delivered through an Agile project. A theme can be compared to a project and includes more than one epic. The Lifecycle of a Theme starts as an idea in the funnel (see article DevOps Plan – Planning ).

Epic

An epic is a description of a chunk of the functionality that includes more than one DevOps cycle. Epics are used to define the roadmap. Epics are the building blocks of a theme and are broken down into features. An epic can be compared with a phase plan of a project.

Feature

A feature is a description of a piece of work that should not cost more than half a DevOps cycle time. A feature is described in business terms. Features are the epic building blocks and are segmented into stories.

Story

A story is a technical description of an object to be realized or the configuration of an object. A story is comparable to a Request for Change (RFC).

Userstory

A userstory is a protocol to describe a theme, epic or feature. The format of a userstory is:

I as < role >

Want to < needs >

So that <added value >

Requirement

Requirement is a demand imposed on an information, application or infrastructure object or service. A requirement can be functional and non-functional.

Test types

The following test types are often used:

UT = Unit Test

ST = System Test

SIT = System Integration Test

FAT = Functional Acceptance Test

PAT = Production Acceptance Test

PST = Performance Test

Concepts for DevOps Plan

Traceability

DevOps is an approach that will accelerate the time to market. For business-critical services it is important to quickly determine what is failing and how to fix it whilst resetting the previous version is not always possible or advisable. The concept of traceability is therefore very relevant for DevOps.

Traceability means that an incident in the production environment must be traceable to the original change of functionality / quality. This requires that:

- Objects in the production environment have a unique identification (ID)

- Generated incidents contains meta data provides immediate insight into the object ID of the source of the incident (see article DevOps Architecture – Monitoring)

- Of each unique identifier knowledge is stored on when it was last modified (build ID)

- Of each build the underlaying source files are identifiable

- Of all source data files it is clear which static requirements were applicable and what the test results were for those source files.

- A requirement is always linked to a feature and where applicable to an epic and a theme.

This form of traceability refers to the backwards traceability. Alternatively, foreward tracking can be used to determine which objects need to be modified if a requirement changes.

Reusability

For an organization, the re-use of functionality is of great importance because it save a lot of time. Furthermore, the re-use of functionality is also important for quality control because existing objects are generally more stable than new objects. By providing metadata requirements, they are easier to detect and use.

Best Practices for DevOps Plan

Start working with DevOps is a journey which starts with learning the fundamentals. After some time people learn and the DevOps process get mature. This is a natural way of working which can be defined as a bottom-up approach in which each DevOps teams finds it way. This is a very good example of a self-learning team. Even some organisations choose to not have any line management in place anymore. Another approach is to look from an architectural perspective to the formation of the DevOps organisation. Where do we want to end? The advantage of defining a rough target architecture of our organisation is that we can define a transition plan and milestones. They are not carved in stone and are only roughly described so that each DevOps team still have their learning curve in their journey. However important risks can be managed well and investments are more future proof. In this article such a target architecture is described. In this case it concerns the information architecture around the subject “traceability” of the DevOps team in order to prevent information debt.

Lifecycle management

The life cycle of a requirement starts during the creation of a theme in the funnel where the functional and quality requirements are not yet concrete. The theme is usually not described in the form of a user story. During the drafting of the product roadmap, the functional and quality requirements are becoming more concrete. The theme is then broken down into epics. The functional and quality requirements are expressed in the features in the format of a user story. However, the features only describe the deliverables in business terms. Finally, the translation to stories gives the opportunity to state the technical requirements.

Functional and technical design

The features are fitted with acceptance criteria that can be used to create the FAT and UAT test plans. Because the features are formulated in business terms, they are not suitable for forming the PAT test plans. Therefore, features needs to be broken down into stories.

It is important to realise that features are not suitable for replacing the functional design. Also, the stories are not a substitute for a technical design. Sometimes a feature refers to a functional design and in stories references are made to a technical design. However, this is not a recommended approach because there is a disconnection between the feature / story described in a tool and a functional / technical design document stating the actual specification.

It is much better is to equip a feature with a set of functional and non-functional requirements making it an independent object with its own identity. Within most tools, it is possible to link requirements to features. The same goes for a story that defines the technical requirements.

Test cases

Both functional requirements and technical requirements must be linked to test cases to ensure that a requirement is actually realized in accordance with the stakeholder’s intention (features) and the technical requirements (story).

Traceability

DevOps provides a fast feedback cycle from requirement to deployment. It is essential that a service disruption is linked to a new or changed requirement (backwards traceability) as soon as possible. But the effect of a new or changed requirement on the already deployed functionality is also of utmost importance (forward traceability).

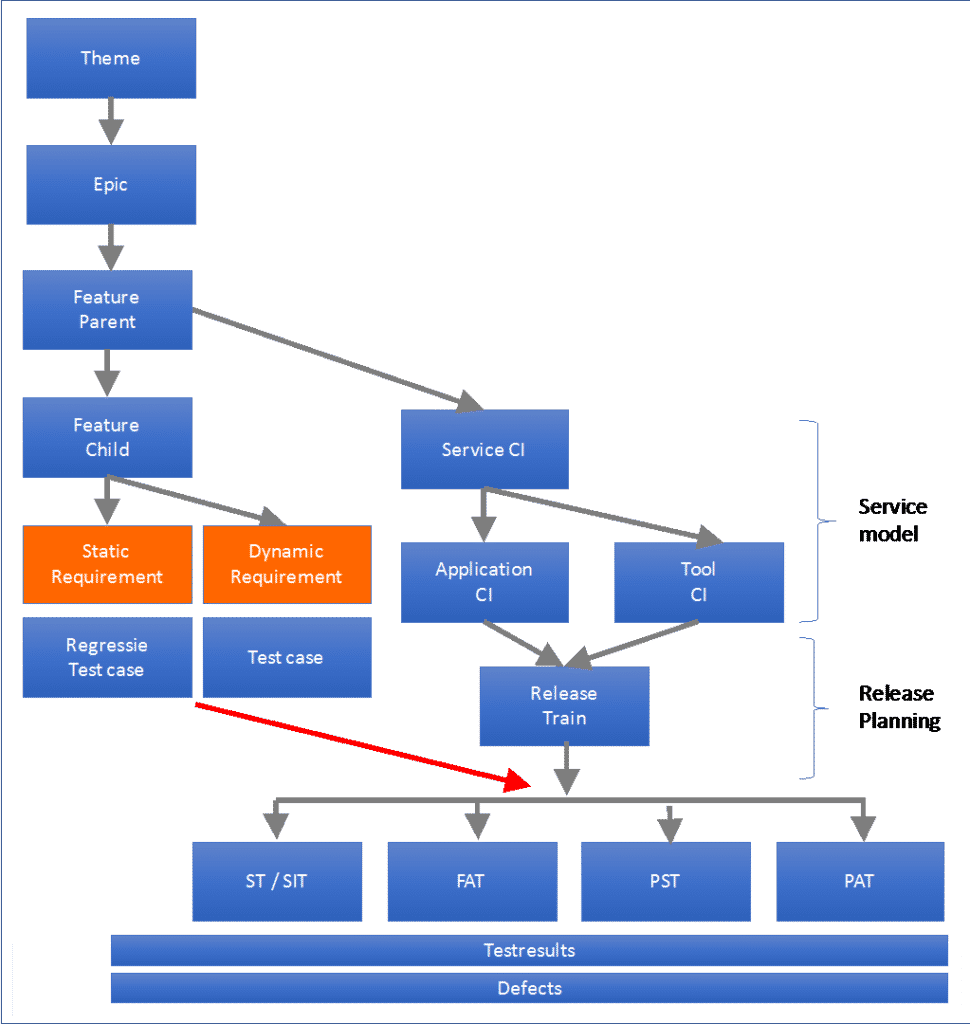

In order to enable both forms of traceability, there must be an excellent registration of the objects from the theme up to the configuration item (CI) in production. In Figure 1 a model of objects and the relationships between them has been drawn up. When choosing a DevOps tooling (see DevOps tooling article), it is very important to note which tools contain which objects and how to link them to where necessary.

Traceability begins with the theme. A theme consists of one or more Epics. The same applies to the Epic and Feature relationship. Because a feature can often be split into segments of functionality, it may be useful to construct a 1:n relationship here. Because a feature is described in business terms, the relationship between Service Configuration Items (Service CI) and feature is the most obvious.

Features and requirements have a 1:n ratio. A requirement may be temporary and apply only to the cycle in which the functionality is realised (dynamic) or lasting and required for the entire life cycle of the feature (static). A static requirement is linked to a regression test case and a dynamic requirement to a normal test case.

A Service CI consists of one or more Application CIs and Tool CIs. Together, this is a service model that divides the service into technical components. The infrastructure CIs are omitted from this drawing in order to keep the picture readable. The deployment of objects preferably takes place at a fixed pace. That is why the metaphor of a train is very convenient. A CI is rolled out by placing it on a release train.

Whether or not a Service CI is deployed with the release train is determined based upon the quality of that Service CI. The testing is based on the various test types (ST, SIT, FAT, PAT, PST).

The ST and SIT take place in the test environment. The FAT, PST and PAT in the acceptance environment. The test cases are linked to a requirement as well as to an object (Application CI and / or Tool CI). Finally, the test results are linked to the test cases and the defects to the test results.

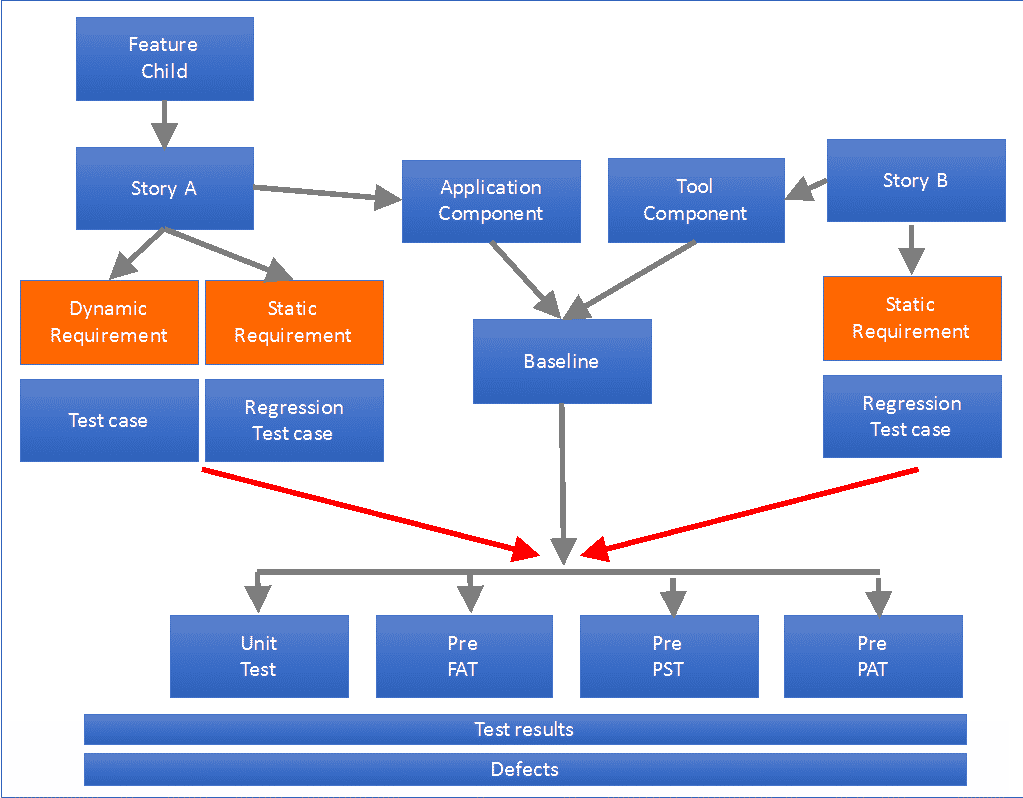

Figure 2 shows a further detailed view of figure 1. Herein the stories are related to the features. Also, the test types are of lower granularity. The FAT / PAT and PST are provided with the word “pre”, which indicates that these test types are not the actual FAT / PAT and PST but an early test of the acceptance test in the test environment.

Information debt

An important risk that few organizations recognise is information debt. This is a phenomenon in an Agile project that results from the inadequacy of the administration of meta data of the objects shown in Figures. 1 and 2. The result of this gap is that the tools that will be deployed in the deployment pipeline over a number of months cannot function because meta data is not recorded. The result is manual testing or poor testing. Therefore, it is justified to state that most DevOps teams are currently producing legacy.

Discuss with us about this article on LinkedIn.

More information

Related Books:

DevOps Best Practices, ISBN: 9789492618078

Agile Service Management with Scrum, ISBN: 9789071501807

Related training sessions:

- DevOps Foundation

- DevOps in practice

- DevOps Master

- Masterclass DevOps Operations

- Masterclass DevOps Application Development

- Masterclass DevOps Architecture

Related Article:

Mogelijk is dit een vertaling van Google Translate en kan fouten bevatten. Klik hier om mee te helpen met het verbeteren van vertalingen.

Laatste artikelen

- De IT-offerte: Waar moet je op letten bij Software en SaaS?

- De ICT-checklist voor het moderne kantoorgebouw

- De paradox van Cloud FinOps Governance: kostenbeheersing in de cloud

- De mens als AI agent: van meester naar slaaf

- Exploratief testen: Agile softwaretesting zonder testscripts

- DRY Principe: Fundament voor Schone Code en Onderhoudbare IT

- Citizen Developer Governance: Veilige Low-Code/No-Code voor medewerkers en compliance

- Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS): Noodstroomvoorziening voor IT-Infrastructuur

- De Cloud Security Baseline: 10 kritieke auditpunten voor AWS, Azure en GCP

- Model Drift: de onvermijdelijke veroudering van AI-modellen