DevOps Architecture – Tooling portfolio

Gerelateerde artikelen

Tooling portfolio:

DevOps Tooling portfolio Introduction

This article describes how application and infrastructure architecture can contribute to the choices of the DevOps tooling portfolio.

DevOps Tooling portfolio Definitions

A tool portfolio is an overview of tools. Based on this portfolio, we can analyse where tools are missing, where tools are redundant and where the tool has dual functions. An important aspect of this is the prevention of function and quality loss within the DevOps teams due to poor collaboration of the tools.

Make or buy:

Maintaining the tool portfolio also involves checking whether to develop or purchase a tool. Often it is not a black and white choice. It is a choice between customizing purchased tool and buying a more expensive tool that already has many features available.

Best of breed / Integrated tooling

An important choice is whether the tools should be selected by function (best or breed) or looking at one or more tools that together cover all the functions.

DevOps Tooling portfolio Concepts

Lifecycle management

Tools, like people, have a lifecycle. Gartner’s hypecycle is an important instrument to analyze in which life cycle step the tool is positioned. The adoption of brand new tools in the market has the advantage that many new technologies and insights are available in the new tools. The downside is the slight adoption by the market, which means that a tool may not be adopted and disappears from the market. Also, the stability of such a new tool is often less because growing pain still have to be eliminated.

DevOps Tooling portfolio Best Practices

Ownership

The tool portfolio must have an owner. Often, each DevOps team wants to claim to be the owner of their own tools because the teams must be and want to have a self-organizing ability. Both developers and system administrator have certain tool preferences. On the other hand, in an organization teams must often work together, for example, because there is a chain in which DevOps teams work or if there is a large long-standing program. In that case, it is important that the same tools are used by the DevOps teams.

Therefore, it is important to build layers in the tool portfolio. The first layer are tools used generic, such as a service desk tool, deployment tools and scheduler. This layer of the tool portfolio is often owned by architecture. This means that all teams have to make use of this tooling. A second layer then consists of a set of tools for a certain functionality from which a selection can be made. Often these tools are only fulfil a part of a particular function. For example, a monitor facility specifically designed to monitor Java applications can be selected by one team while another team chooses another tool because it is better suited for measuring a network. Architecture must ensure that this set of tools works well together and, for example, write their events to a central event manager. Finally, there is a third layer in which the employees themselves can make their own choice. This is necessary to fill in the gaps in the portfolio. But it is also necessary because there must be room for innovation.

DevOps Portfolio framework

To determine the completeness of a portfolio, it is important to look at the application of the tooling. For DevOps, you can look at the process steps of DevOps (see article DeVOps process). By determining the required functions per process step, a measure will be created to map available tools. Table 1 gives an overview of the monitor functions that 10 organizations have recognized.

| DevOps process | Function |

| Plan | Feature admin Product backlog Sprint backlog Dashboard Change management |

| Code | Software configuration management Code repository Version management Baselining |

| Build | Continuous integration |

| Test | Issue tracking Test cases Test scripts Regression tests |

| Release | Security management |

| Deploy | Release and Deployment management Continuous delivery DTAP management |

| Operate | Incident management Problem management Configuration management |

| Monitor | Reporting |

Table 1. DevOps tool functionality.

DevOps Portfolio analysis

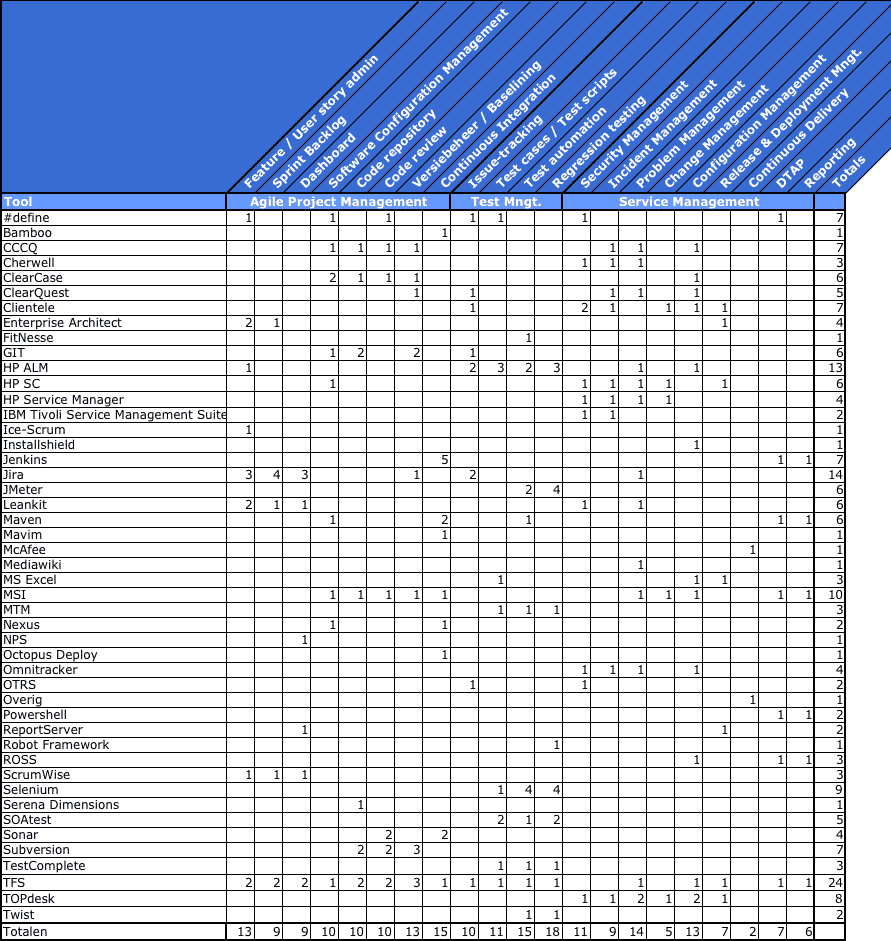

Figure 1 gives an overview of the tools used by ten organizations. The number of tools is quite infinite. Also, many tools have more than one functionality.

DevOps Tooling portfolio Pitfalls

1. Silo selection.

Best of breed is often chosen. This is especially true for DevOps teams with immature DevOps processes because the work is still ad hoc and not integrated. However, as soon as a process becomes more mature and the steps in the process requires more and more information transfer, the need for automation also increases. Often, then, it appears that tools cannot be connected so easily or not at all. Therefore, there is a trend in the market to look into integrated solutions so that this problem does not occur. One disadvantage of these integrated tools, however, is that certain aspect areas may contain less extensive functionality. Which tools provide integrated solutions is easy to derive from Figure 1, by looking at how many features one tool offers. For a good selection, however, you must look at each function that is marked as important to the process. There may still be holes that need to be sealed with additional tools and links.

2. Bottom up.

A big pitfall is that all DevOps teams choose their own tooling as soon as a need pops up. In many cases there is a need for information exchange between DevOps teams after some time, which seems not to be possible of very costly to accomplish. It often appears that standardization after all would have been better. Developers and system administrators, however, adopt their tools like teddy bears. Often a considerable amount of time is spent in upgrading the tools. As a result, they get the feeling being the owner of the tool. The consequence is that tools are not substituted by new and more standard out of the box functionality. They rather keep going on to develop and connect tools while better standard solutions are available in the market.

3. Make or Buy

Not many service organizations build themselves. Custom made tools and plug-ins are, however, quite common. By definition, there is always something to configure and there is always a need to connect tools. The question is, however, how much time and energy is involved and whether the required (integrated) functionality is not already in the market. In addition, an employee lock in is created because there is only one specialist who can keep the tool running.

Discuss with us about this article on LinkedIn.

More information

Related Books:

DevOps Best Practices, ISBN: 9789492618078

Agile Service Management with Scrum, ISBN: 9789071501807

Related training sessions:

- DevOps Foundation

- DevOps in practice

- DevOps Master

- Masterclass DevOps Operations

- Masterclass DevOps Application Development

- Masterclass DevOps Architecture

Related Article:

Mogelijk is dit een vertaling van Google Translate en kan fouten bevatten. Klik hier om mee te helpen met het verbeteren van vertalingen.

Laatste artikelen

- De IT-offerte: Waar moet je op letten bij Software en SaaS?

- De ICT-checklist voor het moderne kantoorgebouw

- De paradox van Cloud FinOps Governance: kostenbeheersing in de cloud

- De mens als AI agent: van meester naar slaaf

- Exploratief testen: Agile softwaretesting zonder testscripts

- DRY Principe: Fundament voor Schone Code en Onderhoudbare IT

- Citizen Developer Governance: Veilige Low-Code/No-Code voor medewerkers en compliance

- Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS): Noodstroomvoorziening voor IT-Infrastructuur

- De Cloud Security Baseline: 10 kritieke auditpunten voor AWS, Azure en GCP

- Model Drift: de onvermijdelijke veroudering van AI-modellen